Introduction

Athletes competing at the national and international level face loneliness, pressure from parents and coaches, and a lack of leisure time and contact with family during practice and competition, which are in addition to excessive hours of training, travel and competitions (Madigan et al., 2019). These situations bring high-intensity emotions and feelings, such as anxiety, worry, and stress which must be controlled by athletes in order to cope with and adapt to their feelings (Madigan et al., 2020). Stressful situations require the development of strategies to deal with them in order not to let stress negatively affect performance. The cognitive processes of recognition, evaluation and confrontation of stress situations is termed coping, a theme that has received considerable attention in the sport context as the process by which athletes respond consciously to internal and external demands associated with sports participation (i.e., the process of control over stressful situations) (González-García and Martinent, 2020).

When athletes have difficulty coping with stressful situations that happen chronically, they may experience burnout, which causes both physical and psychosocial disorders (Gustafsson et al., 2017). Burnout is a syndrome derived from stress and characterized by psychological, emotional and even physical withdrawal of formerly pleasant and desired sport participation (Smith, 1986). Furthermore, burnout is a response to exhaustion from the frequent efforts related to excessive training and competition demands of each season (Raedeke and Smith, 2001). As a result, athletes can develop a state of exhaustion that tends to negatively impact performance.

Burnout syndrome can be explained by the interaction between three dimensions: physical and emotional exhaustion, reduced sense of athletic accomplishment, and sport devaluation. Exhaustion is related to intense demands for training and competitions. The reduced sense of accomplishment is fundamentally interpreted as dissatisfaction related to sports ability, skills and performance. Sport devaluation consists in lack of interest, lack of desire and lack of concern about sport (Raedeke, 1997). Empirical studies obtained evidence of burnout in athletes who were considering attrition (i.e., dropout) (Cresswell and Eklund, 2005; Isoard-Gautheur et al., 2016). Thus, the dropout must be considered as one of the main consequences of burnout (Goodger et al., 2007). Although burnout syndrome studies are relatively new in the context of sport (Gustafsson et al., 2014), there are several studies that aimed to implement and analyze measurement questionnaires (Gerber et al., 2018; Raedeke and Smith, 2001) and to investigate the relationship between burnout and psychosocial variables (Madigan and Nicholls, 2017).

It is worth mentioning that there is a divergence in the theoretical foundation of burnout involving the investigations of coaches and athletes. Studies with coaches are more aligned with the literature of work psychology, since their training, teaching, interpersonal and leadership tasks are similar to those observed in the helping professions. On the other hand, athletes do not have characteristics inherent to helping professions, such as the need to promote biopsychosocial advances in other people, a reason that makes the study of the syndrome from the classical paradigm of general psychology inappropriate. For this reason, burnout among athletes is interpreted mainly as an individual psychological process (Goodger et al., 2007).

Most researchers have investigated burnout in athletes following cross-sectional or retrospective designs. The results have shown that between 2 and 6% of male athletes and between 1 and 9% of female athletes experienced high level symptoms of burnout (Gustafsson et al., 2007). To date, an increasing number of studies have examined interactions between burnout and coping from a longitudinal perspective. Recent research highlighted that avoidance coping (withdrawal from dealing with stressful events) predicted increases in athlete burnout, whereas problem focused coping (strategies that aim to solve the stressful situations) was unrelated to changes in athlete burnout (Madigan et al., 2020). Thus, it is possible to understand the behavior of athletes toward specific demands of different periods of a sport season.

This research considered the perceptions of burnout dimensions and coping strategies in a longitudinal perspective, and it evaluated the correlation of temporal burnout and coping strategy characteristics in athletes. Recent research correlated burnout and mental toughness (Madigan and Nicholls, 2017), as well as variables of burnout and coping in college volleyball players, in a longitudinal design (Schellenberg et al., 2013). However, the season was relatively short (approximately 3 months), and the subjects did not participate in high-level competitions; hence, the situation may not have had the appropriate conditions for the syndrome of burnout. In a more complex design, the present research assessed burnout and coping scores of high-level volleyball players at four time points over a 10-month sport season. We expected an increase in burnout dimensions over time, as well as a decrease in coping strategies. Finally, based on previous research that supported the hypothesized associations between burnout and coping in sport (Madigan et al., 2020), we expected negative relationships between burnout and coping variables during the season.

Methods

Participants

Fifty-four athletes (twenty-eight men and twenty-six women, age M = 25.57, SD = 4.72, range 18-35) were recruited from six professional volleyball league teams. The response rate was 67.5%. The number of participants was similar to other longitudinal studies on this topic (Cresswell and Eklund, 2005, 2006). Moreover, athletes were required to meet three criteria in order to participate in the study. First, participants were required to compete in national and/or international level competitions. This choice is justified by the fact that athletes who compete at national and international levels are exposed to higher competitive demands, training, injuries, and constant media appearances, which can increase stressful situations and result in burnout, as compared to athletes that compete at regional or college levels. Second, participants were required to have at least five years of competitive sports practice, which characterizes high-level athletes and is relevant for burnout research, since the syndrome is a response to chronic stress. Third, participants were required to be present for each data collection (see "Design and Procedures" section). Athletes who were injured and thus, did not compete throughout the season were not included in the study. Additionally, athletes who were competing for national volleyball teams during one or more of the data collection points were also excluded. The University Ethics Committee approved this study which respected all the standards set by the National Board of Health for research involving humans, as well as American Psychological Association (APA) procedures.

Measures

Burnout was measured through the Athlete Burnout Questionnaire (ABQ) (Raedeke and Smith, 2001), which consists of fifteen items that assess the frequency of feelings related to burnout. Each item refers to a subscale of the syndrome manifestation in athletes (Gerber et al., 2018; Raedeke, 1997): physical and emotional exhaustion (PEE), reduced sense of athletic accomplishment (RSA), and sport devaluation (SDE). Answers are given on a Likert scale ranging from "almost never" (1) to "almost always" (5), with three intermediate ratings. The ABQ has shown good construct validity and high internal consistency (Gerber et al., 2018; Raedeke and Smith, 2001). We adopted the ABQ language version, which was validated through three methodological steps (Pires et al., 2006): back translation of the Athlete Burnout Questionnaire to the language; validation through construct validation (exploratory factor analysis); and assessment of the reliability. The data obtained confirmed both construct validity and reliability. Moreover, the validated version exhibited acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach's α coefficients for the items of the instrument ranging between 0.79 and 0.81) and construct validity.

Coping was measured through ACSI-28BR (Miranda et al., 2018), the language version of the Athletic Coping Skills Inventory (ACSI-28). This is a twenty-eight item questionnaire covering thoughts and actions that athletes use to deal with internal or external demands of the sporting context (Smith et al., 1995). Each item refers to one of the seven factors that represent coping strategies in sport: Coping with adversity (CA); Peaking under pressure (PP); Goal setting/mental preparation (MP); Concentration (CO); Freedom from worry (FW); Confidence/achievement motivation (CM); and Coachability (COA). The answers are given on a Likert scale ranging from "almost never" (0) to "almost always" (3), with two intermediate ratings.

Design and Procedures

The first step for applying the set of instruments was to produce a list of volleyball athletes who were competing at international and/or national levels. Subsequently, these athletes and their coaching staff were contacted to explain the objectives of the study and request permission from coaches to ask their athletes to participate. After this contact, athletes who were available for the study participated in data collection that was held in a private room, to minimize external interference and respect the individuality and comfort of each participant.

Data collection was carried out at four time points, which were distributed throughout a year of the sport season. However, the importance of the competitions increased from the first to the last data collection. The first data collection moment (M1) was in the preseason (June and July). The second moment (M2) was during the State Championships and/or during friendly games that served as preparation for the National Volleyball League (September and October). The third moment (M3) was during the first leg of the National Volleyball League (December and January). Finally, the fourth moment (M4) was during the last leg of the National Volleyball League and the Continental Club Championship (February, March, and May).

Statistical Analysis

Demographic data were analyzed by descriptive statistics (percentage, mean and standard deviation). The data normality was assessed by the Shapiro-Wilk test. The dependent variables related to burnout and coping strategies were determined using the Friedman test analyzing the four moments discussed previously, and the Dunn post hoc test was adopted for pair wise comparisons. The Spearman correlation coefficient (rho) was applied to verify the relationship between burnout and coping dimensions at the four moments. A minimum critical rho > 0.4 was considered to be valid for the analysis of the correlation between variables. This value corresponds to the lower limit of moderate intensity for the correlation between variables (Hair et al., 2009). All statistical procedures were calculated by the Prisma statistical package, version 6 (GraphPad Software Inc, San Diego, CA). The level of significance was set at p < .05.

Results

Before the main analysis, the assessment of the internal consistency of the instruments (Cronbach’s alpha) supported the reliability for burnout (physical and emotional exhaustion α = from .73 to .91, reduced sense of athletic accomplishment α = from .68 to. 83, sport devaluation α = from .42 to .83). The reliability for coping was lower for the concentration and coachability dimensions (coping with adversity α = from .57 to .81, peaking under pressure α = from .76 to .82, goal setting/mental preparation α = from .71 to. 84, concentration α = from .26 to .50, freedom from worry α = from .52 to .77, confidence/motivation α = from .53 to .72, coachability α = from .44 to .62).

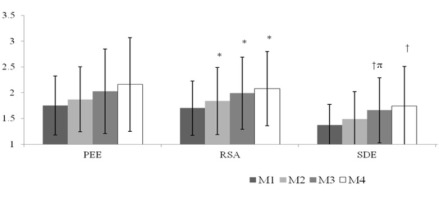

In the present study, burnout scores were obtained at four time points of the season. The data did not present a normal distribution, which led to the use of the Friedman test for verification of significance when comparing the scores at the four moments of the season. Because the Friedman test is a nonparametric test, mean scores were not analyzed, and instead medians and ranks were used. Figure 1 shows the burnout variable data of the volleyball athletes.

Figure 1

Burnout variables data (mean and standard deviation) of volleyball players (n = 54). PEE = Physical and emotional exhaustion; RSA = Reduced sense of athletic accomplishment; SDE = Sport devaluation; M1 = Moment 1; M2 = Moment 2; M3 = Moment 3; M4 = Moment 4. * p < 0.05 (compared to M1); † p < 0.05 (compared to M1); π p < 0.05 (compared to M2).

The median frequency of the physical and emotional exhaustion dimension ranged between almost never and rarely at M1, M2 and M4, while there was an increase for the rarely frequency at M3. The reduced sense of athletic accomplishment dimension showed frequency variation between almost never and rarely at M1 and M2 but at M3, presented as rarely, and at M4, the score raised to the interval between rarely and sometimes.

The analysis of the sport devaluation dimension at the four moments showed average values ranging from almost never to rarely. Therefore, at M1 and M2 scores of all the athletes were in the lower syndrome frequency range, indicating a reduced occurrence of the burnout dimensions. Small frequency increases for the physical and emotional exhaustion and reduced sense of athletic accomplishment dimensions were observed at M3, and the latter dimension also showed an increased frequency at M4.

Aside from the physical and emotional exhaustion dimension (X2 = 7.37; p = 0.06), significant differences were observed in other burnout dimensions. The perceptions of reduced sense of athletic accomplishment (X2 = 20.58; p < 0.01) increased from M1 to M2, M3, and M4. The perceptions of sport devaluation (X2 = 19.83; p < 0.01) increased from M1 to M3 and M4, as well as from M2 to M3.

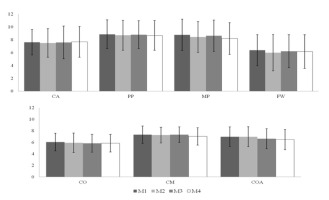

To complement the investigation about the behavior of burnout throughout the season, it becomes relevant to assess coping strategies with the aim of understanding how athletes face stressful situations that can lead to burnout. Figure 2 presents descriptive data of the coping variables. The data did not present a normal distribution, which led to the use of the Friedman test for verification of significance when comparing the scores at the four time points during the season.

Figure 2

Coping variables data (mean and standard deviation) of volleyball players (n = 54). CA = Coping with adversity; PP = Peaking under pressure; MP = Goal setting/Mental preparation; FW = Freedom from worry; CO = Concentration; CM = Confidence/Motivation; COA = Coachability; M1 = Moment 1; M2 = Moment 2; M3 = Moment 3; M4 = Moment 4.

Comparing M1, M2, M3 and, M4, there were no significant differences in any of the coping strategies throughout the season: coping with adversity (X2 = 0.03; p = 0.99); peaking under pressure (X2 = 2.19; p = 0.53); goal setting/mental preparation (X2 = 5.18; p = 0.06); freedom from worry (X2 = 0.56; p = 0.91); concentration (X2 = 3.23; p = 0.36); confidence/motivation (X2 = 4.83; p = 0.19); and coachability (X2 = 4.28; p = 0.23).

In regard to the possible correlations between burnout and coping variables, normality analysis indicated a nonparametric distribution of the data, as it was derived from ordinal scales. Accordingly, the Spearman correlation coefficient was adopted for the data analysis. Table 1 presents the correlations between burnout dimensions and coping dimensions at M1, M2, M3, and M4.

Table 1

Correlations between burnout and coping variables throughout an annual season.

[i] PEE = Physical and emotional exhaustion; RSA = Reduced sense of athletic accomplishment; SDE = Sport devaluation; CA = Coping with adversity; PP = Peaking under pressure; MP = Goal setting/Mental preparation; CO = Concentration; FW = Freedom from worry; CM = Confidence/Motivation; COA = Coachability. * p < 0.05.

In general, there were significant, negative, and moderate correlations between the reduced sense of athletic accomplishment dimension and the confidence/motivation coping strategy at all times of the season. Unlike the preseason, the first competitive moment (M2) showed a significant, negative, and moderate correlation between the sport devaluation dimension and the coping with adversity strategy. The correlation results at M3 showed the same correlation pattern between the reduced sense of athletic accomplishment dimension and strategies to deal with adversity and goal setting/mental preparation. Finally, thelast season competition (M4) presented significant, negative, and moderate correlations between the coping strategy coachability and the reduced sense of athletic accomplishment and sport devaluation dimensions.

Discussion

The purpose of the current study was to analyze burnout perceptions and coping strategies in a longitudinal perspective over four time points during a sport season and to correlate temporal burnout and coping strategy characteristics in volleyball athletes. The main findings presented a significant increase in the reduced sense of athletic accomplishment and sport devaluation perceptions during the season. However, no coping differences were observed through the longitudinal analysis. Burnout dimensions showed a moderate inverse correlation to confidence/motivation at all measurement points during the season.

In relation to the development of burnout variables through the season, no differences were observed in the behavior of the physical and emotional exhaustion dimension throughout the four moments. This is despite the p-value having reached the level close to the limit of statistical significance. However, differences in the reduced sense of athletic accomplishment and sport devaluation were observed between the moments. Such changes are in agreement with theoretical propositions which point out burnout as a chronic process (Madigan et al., 2020). Therefore, it is possible that the burnout dimension scores may increase over time. This scenario in which athletes evaluate sports practice as a source of stress provides support for the cognitive-affective model of burnout proposed by Smith (1986). According to this model, the imbalance between the demands of a situation and the coping resources to deal with them can lead to stress. Consequently, the maintenance of this imbalance over time will result in burnout.

Because the syndrome is associated with chronic stress, it is possible that burnout dimension scores increase over time. Two factors may explain this change. The first includes the situational demands and the athletes’ perceptions associated with the team environment (Cresswell and Eklund, 2006; Kerdijk et al., 2016). It was observed in this sample of volleyball athletes that the indicators of burnout increased during the first and second legs of the National Volleyball League, the most important competition of the season. Such evidence suggests that the intensity of the competition, with several trips around the country and games twice a week, as well as pressure from sponsors, managers and coaches for positive results in order to rank teams for the playoffs, constitute situational demands which can influence the athletes' perceptions and consequently raise the syndrome indicators. The second factor is the fact that the accumulation of training and competition can trigger chronic stress. As a result of this process, athletes perform a cognitive assessment and begin to perceive an increased burden and charge for positive results, as well as a reduction of earnings and enjoyment in sport, highlighting the burnout cognitive-affective model (Smith, 1986).

In terms of the coping strategy scores over the season, our hypothesis that the scores for coping strategies would decrease over the course of the season was not confirmed. No significant differences were found for coping dimensions between the preseason and competitive moments in volleyball athletes. These results agree with the findings of a study which failed to find differences in soccer players’ coping perceptions over six months (Louvet et al., 2007). While verifying the prevalence of stably adopted coping strategies across three competitions, the authors pointed out the characterization of coping as a trait, in contrast to the state perspective.

Considering the correlations between burnout and coping variables in the preseason (M1) and in the competitive moments (M2, M3, and M4), the negative and moderate correlation between the reduced sense of athletic accomplishment and the confidence/motivation coping strategy provides information that this dimension can be faced through the use of motivation techniques. These findings are in agreement with studies which found a close association between the emergence of burnout and the loss of athlete’s motivation (Fagundes et al., 2019; Gustafsson et al., 2018). Loss of motivation is a result of perceived low rewards and achievements despite high efforts. This perception appears in the cognitive assessment of athletes (Smith, 1986).

In support of our hypotheses, our overall findings suggest that burnout and coping variables are inversely correlated over the professional volleyball season. A similar correlation was observed in college volleyball players (Schellenberg et al., 2013). Problem focused coping strategies may increase the development of skills and mobilize resources that could be used to avoid undesirable stress and burnout outcomes. In addition to the type of strategy employed, other factors such as the interaction between the athlete and the sport environment and the time of the sports season (situational specificity) can influence coping effectiveness in the processes of burnout prevention and control.

A noteworthy limitation of the present study is that athletes were submitted to the burnout and coping assessment based on only one technique (psychometric instruments). For a more detailed analysis, other diagnostic techniques are recommended, such as qualitative interviews. The evaluation of burnout and coping through different techniques allows for a more precise diagnosis (Madigan et al., 2020). Also, the findings of internal consistency were slightly below what was desired, which might be because the language version of the ACSI-28 was developed with athletes from different competitive levels (Miranda et al., 2018). This participants' profile is in contrast to the current study, which evaluated only top-level athletes.

Despite the strengths of this study with respect to its novelty, another potential limitation warrants mentioning: a number of the coping alpha coefficients were found to be weak or marginal. However, this is a recurring historical characteristic in the coping literature. According to Levy et al. (2011), internal consistency coefficients are often reduced because a coping response, from a particular category, may singularly be enough to decrease stress. Therefore, the need to use other coping strategies from the same category is diminished.

Though correlational in its design, the present study offers practical insights. The results suggest that data obtained using correlations may provide more sensitive information about the inverse and moderate theoretical proximity between burnout and coping. The significant increase in burnout perceptions as the season progressed indicates that athletes and their technical staff should be aware of the sport demands and the possibility of burnout symptoms manifesting themselves later in the season. Additionally, the creation of coping interventions necessitates considering a variety of conceptual and practical issues (Reeves et al., 2011) and represents a potentially rewarding endeavor for those interested in promoting athletes’ well-being through burnout prevention and treatment. The findings of previous research suggest that fostering coping strategies such as confidence and motivation may be useful for avoiding burnout (Gustafsson et al., 2018; Madigan et al., 2019).

This study only concentrated on volleyball, but longitudinal research in the area of burnout should be expanded to other sports. Future research should continue to monitor athletes’ levels of burnout, considering such factors as possible differences between play-off versus non-play-off teams, genders (male versus female athletes), and sports levels (professional versus amateur teams). Consequently, studies should aim to formulate prevention strategies for coping with burnout in order to reduce the possibility of decreased performance and to prevent illness, the absence from training and competitions, or retirement from sport.