Introduction

The assessment of oxygen uptake (V˙O2) kinetics and the interpretation of its parameters allow the quantification of the physiological mechanisms responsible for the dynamic V˙O2 response to exercise (on-transient kinetics) and its subsequent recovery (off-transient kinetics) (Jones and Poole, 2013; Özyener et al., 2001). It enables a non-invasive assessment of the control mechanisms of muscle energetics and oxidative metabolism (Jones and Poole, 2013; Rossiter et al., 2005) and, consequently, the effectiveness of a training program, providing relevant information about the exercise tolerance determinants (Poole and Jones, 2012; Zacca et al., 2019). Despite the importance of maximal V˙O2 (V˙O2max) for training control and prescription (Duquette and Adam, 2024), the interpretation of V˙O2 kinetic parameters help researchers and coaches to better understand the responsiveness to training stimuli, particularly regarding the physiological significance of the fast and slow components of the dynamic V˙O2 response (Burnley and Jones, 2007; Fernandes et al., 2024).

Following the onset of a specific exercise intensity, V˙O2 on- and off-transient kinetics may have different profiles. Below and at the anaerobic threshold (AnT), i.e., at low and moderate intensities, the V˙O2 profile, after an initial rise that usually lasts ~15–20 s (phase I or cardiodynamic phase), is described by a mono-exponential function, where an exponential increase is visible (phase II or fast component), followed by a steady-state (phase III) (Monteiro et al., 2020; Özyener et al., 2001; Poole and Jones, 2012). At the recovery period after these exercise intensity domains, V˙O2 presents a similar behaviour, i.e., a rapid decrease until reaching the baseline values. Above the AnT, at the heavy intensity domain, V˙O2 response profile starts to differ from less stressful intensities, being usually described by a bi-exponential function (Özyener et al., 2001; Reis et al., 2012). Here, a second V˙O2 elevation is observed after phase II (after ~90–120 s), known as a V˙O2 slow component (Billat, 2000; Burnley and Jones, 2007), until a delayed steady-state or exhaustion are attained. Different behaviours of the off-transient kinetics have been described, since it is identified by both mono- and bi-exponential functions (Monteiro et al., 2020; Özyener et al., 2001; Pelarigo et al., 2017). At the severe intensity domain, a bi-exponential function is typically observed both during on- and off-transient kinetics, with a V˙O2 slow component with significant amplitude (Jones and Poole, 2013; Sousa et al., 2015; Zacca et al., 2019).

Usually, V˙O2 kinetics has been analysed through mathematical modelling (both for on- and off-transient kinetics) using complex programs, that requires some mastery beyond the knowledge of respiratory physiology (de Jesus et al., 2015; Özyener et al., 2001; Sousa et al., 2011). Considering the importance of giving rapid feedback from experimental testing, it became relevant to create a tool for effective and straightforward analysis of the V˙O2 response during exercise. Therefore, VO2FITTING, a validated, free and open-source software, was developed to characterize V˙O2 kinetics during continuous exercise (e.g., running, cycling or swimming), allowing to dynamically edit, process, filter and model the typical V˙O2 responses (Zacca et al., 2019). However, it did not include the possibility of analysing the exercise V˙O2 off-transient kinetics that can provide additional information on gas exchange dynamics, aiding to better interpret the physiological events supporting the V˙O2 on-transient response (Jones and Poole, 2013).

The V˙O2 off-transient kinetics also becomes very useful when the backward extrapolation method is applied, e.g., allowing swimmers to perform without a breathing mask and perform flip turns, achieving competitive velocities, since the testing environment is more ecological (Ribeiro et al., 2016). The aim of the current study was to present an updated version of VO2FITTING software that allows to dynamically process V˙O2 post-exercise data of a large spectrum of exercise intensities, demonstrating the possibility to equally analyse and model V˙O2 recovery data. In addition, we aimed to contribute to the existent knowledge about the V˙O2 on/off symmetry by directly comparing the exercise and its subsequent response at low, moderate, heavy and severe intensity domains. We hypothesized that an on/off symmetry would be observed at low and moderate intensities, while above the AnT, i.e., at heavy and severe domains, different exponential models for the exercise and recovery phases would be evidenced.

Methods

Development and Validation of VO2FITTING Software for Post-Exercise Data Analysis

The already available VO2FITTING software (Zacca et al., 2019) was extended for V˙O2 off-transient kinetics analysis and a swimming experiment was conducted to illustrate how it can be used to edit, process, filter and model the

V˙O2 post-exercise data. The respective installation instructions and other documentation are available at https://shiny.cespu.pt/vo2_news/, and the corresponding author can be reached for further follow-up. Validation V˙O2 datasets were developed for post-exercise data involving two mono- and two bi-exponential widely used mathematical models for describing different intensity transitions (Özyener et al., 2001; Pelarigo et al., 2017; Sousa et al., 2015). V˙O2 was used in a raw form as input, without any filtering or processing, and the models were applied without any parameter constraints.

Participants

Ten trained swimmers (five male) voluntarily participated in the current study, all being engaged in ≥ five swimming training sessions per week. Their main physical characteristics were 16.1 ± 1.7 vs. 15.3 ± 1.2 years of age, 64.0 ± 6.6 vs. 56.5 ± 6.8 kg of body mass and 174.8 ± 4.6 vs. 163.5 ± 6.0 cm of body height for male and female swimmers, respectively, and 495 ± 80 World Aquatics swimming points of best actual competitive performance at the 400 m freestyle event. Swimmers were informed about the purpose of the evaluations and individual written informed consent was provided before data collection, which was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Sport of the University of Porto (protocol code: CEFADE 25 2020; approval date: 11 November 2020) and performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Design and Procedures

In a 25-m indoor swimming pool (with 27ºC water temperature), and after a 600-m low-to-moderate intensity warm-up, swimmers performed a 5 x 200 m front crawl incremental protocol with 0.05 m•s−1 velocity increments and 3-min passive rest intervals between steps (Carvalho et al., 2020; Fernandes et al., 2011; Monteiro et al., 2020). The velocity of the last step was calculated according to each swimmer’s 400 m front crawl time, with a 0.83-s per turn adjustment (due to the use of the respiratory snorkel) (Ribeiro et al., 2016). Subsequently, four successive velocity increments were subtracted to define the subsequent step paces. Velocity was controlled by a visual pacer with flashing lights in the bottom of the pool (Pacer2Swim, KulzerTEC, Aveiro, Portugal) and measured with a manual stopwatch (Seiko, Tokyo, Japan). In-water starts and open turns without underwater gliding were used as previously described (Monteiro et al., 2020).

Pulmonary gas exchange and ventilation were continuously measured breath-by-breath using a portable gas analyser (K4b2, Cosmed, Rome, Italy) suspended on a steel cable above the water surface and connected to the swimmer by a low hydrodynamic resistance respiratory snorkel and valve system (Aquatrainer®, Cosmed, Rome, Italy). The respiratory variables were continuously monitored for 3 min during the recovery period (Ribeiro et al., 2016). The gas analysis system and the turbine volume transducer were calibrated before the experiments (following the manufacturer instructions) with gases of known concentrations (16% O2 and 5% CO2) and a 3-L syringe (respectively). Lactate concentration [La−] values were obtained using capillary blood samples from the swimmers’ fingertip at rest, immediately after each step and at the 1st, 3rd, 5th and/or 7th min post-protocol until reaching the maximal individual value (Lactate Pro2; Arkay Inc., Kyoto, Japan) (Carvalho et al., 2020; Monteiro et al., 2023).

V˙O2 data were analysed for each incremental protocol step and categorized as low, moderate, heavy and severe intensity domains according to the intensities corresponding to the AnT and V˙O2max (Fernandes et al., 2024). To this end, the lactate-velocity curve modelling method was used to determine the interception point of a combined linear and exponential pair of regressions (Carvalho et al., 2020), while conventional physiological criteria were applied to establish V˙O2max (de Jesus et al., 2015; Howley et al., 1995). Therefore, the low and moderate exercise domains were identified as corresponding to the step below and the step at the AnT (respectively), and the heavy and severe domains as corresponding to the step below and the step where V˙O2max was elicited (respectively) (de Jesus et al., 2015; Pelarigo et al., 2017).

V˙O2 off-transient kinetic parameters were estimated by bootstrapping and the goodness of fit of each model was analysed with raw data by only excluding errant breaths (Lamarra et al., 1987; Sousa et al., 2015). The off-transient for each intensity domain was estimated with two mono- and two bi-exponential models (Equations 1–4, respectively), and the one that best fitted the data by presenting lower standard error of regression was selected:

where V˙O2(t) (mL•kg−1•min−1) is V˙O2 normalized to the body mass at the time t, EEV˙O2 is the end-exercise V˙O2 value, Ap and Asc (mL•kg−1•min−1), TDp and TDsc (s), and τp and τsc (s) are the amplitudes, time delays and time constants of the fast and slow V˙O2 components, respectively (Özyener et al., 2001; Sousa et al., 2015), and H represented the Heaviside step function (Ma et al., 2010). To characterize the on/off symmetry response at the different swimming intensity domains, V˙O2 on-transient kinetic parameters were also estimated using VO2FITTING by choosing the model that best fitted to the different intensity swimming efforts from those described in the literature (de Jesus et al., 2015; Özyener et al., 2001; Zacca et al., 2019).

Statistical Analysis

Noisy (gaussian) and non-noisy validation datasets were developed for the four above-referred models to describe the different intensity transitions. Subsequently, V˙O2 data as a function of time were uploaded into the software, verifying whether the fitted parameters perfectly matched the known input values. For the experimental study, a post-hoc power calculation indicated that a sample size of 10 subjects with a large effect size would result in a statistical power of 75% (α = 0.05; G*Power 3.1.9.7; Heinrich Heine Universität Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany). Bootstrapping with 1000 samples was employed to estimate the parameters of mono- and bi-exponential fitting models (a feature available in VO2FITTING). When multiple models were applied to V˙O2 data, an ANOVA F-test was conducted to verify the goodness-of-fit. The mean, standard deviation and the coefficient of variation were calculated for each parameter estimated. A Student’s paired t-test was conducted to test for differences between the on- and off-transient kinetic parameters within each intensity domain and between consecutive intensities, using Cohen’s d standardized effect sizes (ES) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). For the three comparisons between consecutive intensities, a Hochberg (step-up) correction was used to reduce the type I errors (Menyhart et al., 2021). Furthermore, linear regression and Pearson’s correlation (r) and determination (r2) coefficients were also used to assess the relationships between the considered variables. These statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (version 29.0.0.0; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) with a significance level of 5%.

Results

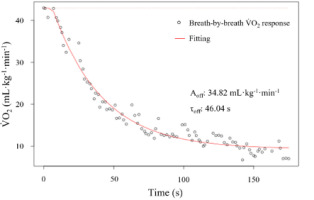

V˙O2 data as a function of time, obtained from the validation datasets, generated perfect fits, with the parameter estimates perfectly matching the known inputted values for all the four available models (standard error = 0; p < 0.001). An example of the different smoothing filters available in VO2FITTING and applied to the V˙O2 post-exercise curve is presented in Figure 1. The mono-exponential models resulted in best fits during swimming and the recovery period for all swimmers, independently of the exercise intensity (Figure 2) since they were the only ones that fitted or because they presented a smaller standard error of regression and a residual sum of squares. Particularly for V˙O2 off-transient kinetics data modelling, the mono-exponential function without TD had the best fit. Mean parameter estimates for all swimmers (individually fitted), standard deviations, and mean coefficients of variation are presented in Table 1. The coefficients of variation of the estimated Aon, Aoff, τon and τoff ranged between 1.4–2.7, 1.8–5.4, 18.1–26.0 and 5.6–15.1%, respectively, and 4.5–11.5% for TDon.

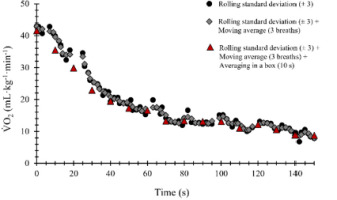

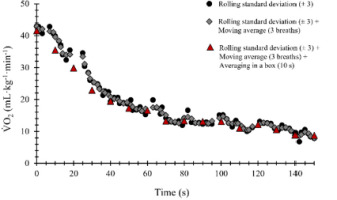

Figure 1

Example of oxygen uptake (V˙O2) recovery curve smoothing using different available filters in VO2FITTING.

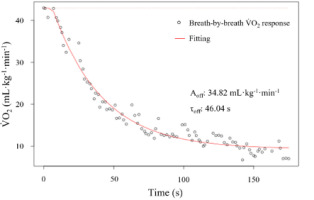

Figure 2

Representation of a recovery oxygen uptake (V˙O2) to time curve response using VO2FITTING with the respective amplitude (Aoff) and time constant (τoff) identified, using the mono-exponential model without time delay.

Table 1

Estimated V˙O2 on- and off-transient kinetic parameters at the low, moderate, heavy and severe swimming intensity domains.

| Low | Moderate | Heavy | Severe | Low vs. Moderate | Moderate vs. Heavy | Heavy vs. Severe |

|---|

| p | ES (95% CI) | p | ES (95% CI) | p | ES (95% CI) |

|---|

| V˙O2peak (mL•kg−1•min−1) | 39.0 ± 6.1 | 42.2 ± 4.4 | 48.0 ± 3.4 | 51.4 ± 1.3 | 0.03 | −0.8(−1.5 to 0.1) | < 0.001 | −2.2 (−3.4 to −1.0) | 0.001 | −1.5(−2.4 to −0.6) |

| EEV˙O2(mL•kg−1•min−1) | 38.8 ± 4.9 | 38.9 ± 8.1 | 46.3 ± 6.2 | 51.0 ± 8.4 | 0.97 | −0.01(−0.6 to 0.6) | 0.006 | −1.1(−1.9 to −0.3) | 0.07 | −0.7(−1.3 to 0.1) |

| p | 0.91 | 0.06 | 0.45 | 0.81 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| ES (95% CI) | 0.04(−0.6 to 0.7) | 0.7(−0.02 to 1.4) | 0.3(−0.4 to 0.9) | 0.1(−0.6 to 0.7) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Aon(mL•kg−1•min−1) | 31.6 ± 3.9 | 33.2 ± 5.9 | 38.4 ± 5.6 | 40.3 ± 6.1 | 0.32 | −0.3(−1.0 to 0.3) | < 0.001 | −2.0(−3.1 to −0.9) | 0.01 | −1.0(−1.8 to −0.2) |

| Aoff(mL•kg−1•min−1) | 30.1 ± 5.8 | 29.9 ± 7.4 | 36.0 ± 5.7 | 40.3 ± 7.0 | 0.96 | 0.02(−0.6 to 0.6) | 0.03 | −0.8(−1.6 to −0.1) | 0.05 | −0.7(−1.4 to 0.01) |

| p | 0.49 | 0.13 | 0.28 | 0.99 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| ES (95% CI) | 0.2(−0.4 to 0.9) | 0.5(−0.2 to 1.2) | 0.4(−0.3 to 1.0) | −0.004(−0.6 to 0.6) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| τon (s) | 15.8 ± 11.4 | 11.3 ± 2.3 | 13.9 ± 7.0 | 10.3 ± 4.6 | 0.18 | 0.5(−0.2 to 1.1) | 0.17 | −0.5(−1.1 to 0.2) | 0.04 | 0.5(−0.2 to 1.1) |

| τoff (s) | 30.8 ± 10.4 | 29.7 ± 8.4 | 28.7 ± 10.8 | 37.0 ± 9.2 | 0.82 | 0.1(−0.6 to 0.7) | 0.85 | 0.06(−0.6 to 0.7) | 0.08 | −0.6(−1.3 to 0.07) |

| p | 0.03 | < 0.001 | 0.002 | < 0.001 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| ES (95% CI) | −0.8(-1.5 to -0.1) | −2.5(−3.8 to −1.2) | −1.3(−2.2 to −0.4) | −2.7(−4.1 to −1.3) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| TDon (s) | 22.4 ± 6.6 | 19.8 ± 4.4 | 20.5 ± 3.4 | 19.6 ± 1.3 | 0.30 | 0.4(−0.3 to 1.0) | 0.69 | −0.1(−0.7 to 0.5) | 0.44 | 0.3(−0.4 to 0.8) |

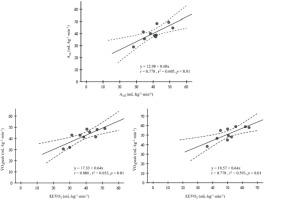

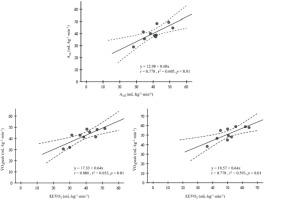

The mean swimming velocities increased with the exercise intensity, corresponding to 1.18 ± 0.06, 1.24 ± 0.06, 1.31 ± 0.06 and 1.40 ± 0.06 m•s−1 for the low, moderate, heavy and severe domains (p < 0.001; ES [95% CI]: −2.6 [−4.0 to −1.3], −2.5 [−3.8 to −1.2] and −3.6 [−5.3 to −1.8], respectively). An increase in V˙O2peak with the intensity rise was observed, while both Aon and Aoff increased from moderate to heavy and from heavy to severe intensities (p < 0.05). When analysing the on/off symmetry, the τon was lower than τoff at all swimming intensity domains (p < 0.05). Significant correlations between on- and off-transient kinetic parameters were observed (Figure 3), with direct associations between Aon and Aoff at severe and between V˙O2peak and EEV˙O2 at moderate and severe intensity domains (p < 0.01).

Figure 3

Relationships between on- and off-transient amplitude (Aon and Aoff) at severe, between peak V˙O2 determined by the last 30 s of swimming (V˙O2peak) and the end-exercise V˙O2 determined by the fitting models and (EEV˙O2) at moderate and severe intensity domains (upper and left and right lower panels, respectively).

Discussion

Despite the importance of V˙O2max assessment (Duquette and Adam, 2024), V˙O2 kinetic parameters’ interpretation is crucial to better understand the physiological response to a given effort (Jones and Poole, 2013). Although different commercial software is available to analyse V˙O2 kinetic data, VO2FITTING is free and open-source, enabling an easier analysis and rapid feedback from continuous exercise, being a useful tool to monitor performance (Zacca et al., 2019). Our results obtained with the validation datasets demonstrated that VO2FITTING allowed to dynamically edit, process, filter and model also V˙O2 post-exercise data with the available features commonly used in V˙O2 kinetic modelling. The addition of this feature permits many advantages like allowing to compare V˙O2 off-transient data with the respective previous exercise phase, with different assessments over time or with different exercise modes.

Breath-by-breath measurements have inherent non-uniformities in the breathing pattern, resulting in some variability around the mean V˙O2 response, known as noise, that can produce some uncertainty in the estimation of the kinetic parameters (Keir et al., 2014; Lamarra et al., 1987). To improve this signal-to-noise ratio and have a clearer and more representative V˙O2 profile, each participant usually performs several exercise transitions that are then time-aligned by interpolating to 1-s time intervals (Lamarra et al., 1987). This tool is available in VO2FITTING, both for on- and off-transient period analysis (Zacca et al., 2019). However, in the current study the incremental protocol was performed only once by each swimmer due to the complexity of the measurements in the aquatic environment. Thus, the estimation of different V˙O2 kinetic parameters from a single transition was carried out using the bootstrapping method that provides reliable information about the estimated parameters (Curran-Everett, 2009; Millet and Borrani, 2009).

Increasing V˙O2peak mean values were observed along the swimming intensity domains spectrum (Fernandes et al., 2006; Monteiro et al., 2023), with the higher amplitude mean values (Aon and Aoff) occurring at heavy and severe compared to moderate and heavy exertions (respectively) being directly linked with the greater V˙O2peak mean values in these latter efforts. Regarding τ, it is a major focus of interest in the V˙O2 kinetic related literature since it indicates the time needed to attain a V˙O2 steady-state, having great importance from a practical perspective and being its accurate estimation highly relevant in the understanding of V˙O2 kinetic on-response control (Carter et al., 2002). An invariant τon is related to a non-limiting oxygen delivery, at least until the heavy intensity domain, and control of muscle kinetics by intracellular processes (Carter et al., 2002; Grassi, 2000). The observed longer τoff seems to be related to a slower rate of response towards reaching the V˙O2 steady-state (Xu and Rhodes, 1999) that can be attributable to the external load on the thorax and increased airway resistance caused by the hydrostatic pressure from water immersion (Leahy et al., 2019), as to a lower muscle oxidative capacity related to the different body position adopted during swimming and recovery periods (Sousa et al., 2015). In addition, it seems that this kinetic parameter tends to remain constant along different intensities (Cleuziou et al., 2003), as it was evidenced in the current study.

Actually, the observed estimated coefficients of variation for Aon, TDon, Aoff and τoff at the four different intensity domains were suitable, as previously reported (Zacca et al., 2019). τon presented slightly higher mean coefficient of variation values, which may be related to the natural variability of V˙O2 response (Cooper and Garfinkel, 2022) and not to the constraints in the breathing pattern while swimming caused by the body position and the aquatic environment, as it was previously thought. In fact, when swimmers used the respiratory snorkel, a loss of synchronization was observed between the breathing pattern and the swimming movement, particularly at higher intensities, indicating that swimmers took advantage from the snorkel to breathe whenever they needed to (and not only when it was possible, as it occurs in free swimming) (Monteiro et al., 2023), approaching what takes place in other exercise modes (e.g., running or cycling).

There is a general consensus in the literature on a mono-exponential response for the low and moderate intensity domains (Cleuziou et al., 2003; Özyener et al., 2001; Poole and Jones, 2012), being consistent with the ideas that O2 debt matches the O2 deficit and of a linear control dynamics (Rossiter et al., 2005). Actually, the AnT is described as the point up to which there is no change or a small increase in [La−] and the V˙O2 steady state is attained following the fast V˙O2 response (Burnley and Jones, 2007; Pelarigo et al., 2017). Above the AnT there is a loss of body homeostasis, with higher participation of the anaerobic metabolism (Carvalho et al., 2020; Pelarigo et al., 2017). Thus, in the V˙O2 kinetic related literature, heavy and severe intensity domains are commonly described by bi-exponential models (Cleuziou et al., 2003; Özyener et al., 2001; Sousa et al., 2015), where a delayed increase in V˙O2 kinetics, known as a slow component, appears after approximately 2–3 min of exercise (Jones and Poole, 2013) as a sign of decreased efficiency of muscle contractions and of the recruitment of fibres with inherently slower V˙O2 kinetics (Grassi et al., 2015; Zoladz et al., 2008).

At these higher intensities (above the AnT), an on/off symmetry is not always verified, contrary to what happens at low and moderate efforts (Özyener et al., 2001; Paterson and Whipp, 1991). However, the results of our experimental study did not evidence any second and delayed exponential increase during exercise nor recovery periods at the different swimming intensity domains. As a consequence of the swimming velocity rise along the incremental protocol, there was an evident decrease in the 200 m step duration (mean ± SD of 169.2 ± 8.0, 161.4 ± 8.1, 152.9 ± 7.0 and 142.8 ± 5.7 s for the low, moderate, heavy and severe intensities, respectively). On the one hand, and despite the 200 m step length validity and practical application during training sessions (Fernandes et al., 2011), the duration of the protocol steps may not have been sufficient to allow the development of the V˙O2 slow component (Jones and Poole, 2013), suggesting that its emergence is closer to the third minute of exercise (Billat, 2000). On the other hand, the predominance of the aerobic component in the swimmers’ training sessions (Santos et al., 2024) may have decreased the V˙O2 slow component due to an increased distribution of type I fibres and an increase in mitochondrial and capillary density (Billat, 2000; Holloszy and Coyle, 1984). In addition, the lack of isometric contractions in swimming and the effort distribution on all four limbs may suggest that no slow component should be expected (Demarie et al., 2001).

Despite the on/off symmetry observed in the present study, since the mono-exponential model presented the best fit, differences between both phases were found, particularly regarding TD. At the transition from rest to exercise, there must be a coordinated pulmonary, cardiovascular and muscular system response aiming to rapidly increase the O2 flux from the atmosphere to muscle mitochondria (Poole and Jones, 2012). Our results are in agreement with a commonly described delay of about 10–20 s, representing the time needed to O2 be unloaded in the muscle and the arrival of the same blood in the pulmonary vasculature for gas exchange (Barstow et al., 1996; Burnley and Jones, 2007). When the exercise ceases, a TD is often described but little interpreted and discussed, being possible to find a high range of mean values along the different exercise intensity domains (Billat et al., 2002; Cleuziou et al., 2003; Sousa et al., 2015).

However, the current results did not evidence a TD at the transition from exercise to recovery, at any of the studied intensity domains. Using VO2FITTING with breath-by-breath data without constraints and smoothing processes, it was possible to choose between different functions the one with the best fit and lower error. In this sense, raw V˙O2 off-transient data with their inherent variability (Keir et al., 2014) demonstrated to be better characterized by a mono-exponential model without TD, indicating that the recovery period started immediately when swimmers stopped after each effort (Sousa et al., 2011) as it has been demonstrated at a muscle level (Behnke et al., 2009). The transition from the horizontal to the vertical position during the intervals and at the end of the protocol seems to facilitate the beginning of the recovery process (Leahy et al., 2019; Sousa et al., 2015), helping to explain the non-delay in our results.

Studies related to V˙O2 kinetics at different exercise intensities and particularly focusing on the V˙O2 slow component and off-transient phase have been carried out mainly in treadmill running and/or with a cycle ergometer (Cleuziou et al., 2003; Jones and Poole, 2013; Özyener et al., 2001), being this topic less studied in swimming. Despite the individual and cyclic characteristics of swimming (like running and cycling), the different environment conditions and the body position seem to affect the V˙O2 kinetic response (Demarie et al., 2001; Leahy et al., 2019). With the use of VO2FITTING, and considering its availability to also analyse the V˙O2 post-exercise data dynamically, we intend to contribute to future challenges, particularly to expand the knowledge about the on/off symmetry and V˙O2 kinetics in such a peculiar exercise mode as swimming. In addition, future works including the comparison of the current methodological approach with only the V˙O2 post-exercise data assessment, also allowing the inclusion of the undulatory underwater phases (Ruiz-Navarro et al., 2024), would add valuable information to this topic.

Conclusions

VO2FITTING proved to be valid for characterizing V˙O2 kinetics not only during continuous exercise, but also during the subsequent recovery period. With this free and open-source software applied for research and performance, it is possible to have rapid feedback about the V˙O2 kinetics parameters without resorting to the use of complex mathematical programming. When characterizing V˙O2 kinetics and the on/off symmetry at different swimming efforts, it seems that protocol steps of 200 m may not be sufficient to observe the development of the V˙O2 slow component at higher intensity domains, particularly in high aerobically trained swimmers. In addition, due to the use of dynamic analysis software it was possible to observe that, after each effort, the recovery started immediately, a fact that could be more evident in swimming due to the body position and environment characteristics. We hope to encourage further research about these less studied topics, particularly in swimming.