Introduction

Vibration exercises typically involve whole-body vibration (WBV), a passive exercise modality in which mechanical stimuli from a vibrating platform are transmitted through the body (Mansfield, 2005). WBV is believed to improve muscle strength. Research indicates that vibratory stimulation can enhance neuromuscular activity, which was confirmed through surface electromyography (Ritzmann et al., 2010). A systematic review concluded that WBV protocols with higher frequencies and amplitudes were more effective in increasing muscle strength (Al Masud et al., 2022). However, the literature has reported inconsistent findings regarding the benefits of WBV, likely because of variations in the intervention type, frequency, amplitude, and duration across studies (Cochrane et al., 2009).

Evidence suggests that WBV offers a range of benefits. It enhances strength and flexibility (Jacobs and Burns, 2009) as well as trunk muscle strength (Maeda et al., 2016) in healthy adults. WBV was demonstrated to improve neuromuscular performance and muscle strength, and thus balance and postural control, in athletes with ankle instability (Coelho-Oliveira et al., 2023). This intervention also supports muscle function through the tonic vibration reflex (TVR), improves muscle energy metabolism through vibration-induced muscle contractions, and increases the muscle perfusion rate and temperature to enhance power (Chena Sinovas et al., 2015; Till et al., 2017).

Similarly to aerobic exercise, WBV may improve cardiovascular endurance (Park et al., 2015). However, whether WBV causes sufficient stimulation to improve cardiorespiratory fitness remains to be determined. Activities such as strength training improve cardiorespiratory fitness by enhancing vascular function, increasing the muscle blood flow, and promoting skeletal muscle adaptations. These adaptations, including vibration-induced muscle hypertrophy, may improve oxygen transport and utilization, thereby enhancing VO2max (Bogaerts et al., 2009). A study indicated that incorporating WBV into exercise regimens confers incremental advantages by enhancing functional capacity, expanding thoracic mobility, and facilitating rehabilitation in patients with a stroke and respiratory dysfunction (Duray et al., 2023). A meta-analysis reported that WBV benefits patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by improving their functional exercise capacity without causing any adverse effects (Cardim et al., 2016).

Limited data are available regarding the effects of WBV on exercise performance in athletes. Some studies have reported that WBV improves lower-limb muscle strength. For example, Annino et al. (2007) demonstrated that short-term WBV improved explosive knee extensor strength in elite ballet dancers. Arora et al. (2021) indicated that WBV, as an additional modality, could enhance the neuromuscular activity of lower-limb muscles in athletes. Colson et al. (2010) concluded that incorporating short-term WBV into preseason training for basketball players increased their knee extensor strength and squat jump (SJ) performance. Karatrantou et al. (2013) reported that WBV enhanced knee flexor mobility and strength in moderately active women. Egesoy and Yapıcı (2023) demonstrated that a 6-week WBV program improved vertical jump and sprint performance in volleyball players.

Unlike the aforementioned studies, a study by Kvorning et al. (2006) revealed that compared with conventional resistance training alone, a combination of WBV with conventional resistance training led to no additional improvements in maximal isometric voluntary contraction or mechanical performance metrics (e.g., jump height, mean power, peak power, and peak velocity) in the countermovement jump (CMJ). Similarly, Bertuzzi et al. (2013) reported that adding WBV to strength training did not significantly improve dynamic strength in long-distance runners. Furthermore, in the study of Martinez-Pardo et al. (2013), WBV at different amplitudes resulted in no significant alterations in vertical jump variables such as height, peak power, and the force development rate.

Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have explored the effects of WBV. A systematic review reported that WBV could improve muscle strength, power, and flexibility (Alam et al., 2018). However, this review did not focus on athletes. Moreover, no meta-analysis was performed because the review included only five studies. A meta-analysis concluded that WBV exerted only small and inconsistent effects on the short- and long-term performance of competitive and elite athletes (Hortobagyi et al., 2015). However, that analysis was conducted in 2015, and several randomized controlled trials (RCT) have been published since then. Another meta-analysis reported that WBV exerted no significant short- or long-term effects on jump performance, sprint performance, or agility in athletes or physically active individuals (Minhaj et al., 2022). However, that study imposed language restrictions during the literature search and did not explore aspects of athletic performance such as muscle strength and cardiovascular endurance.

Considering the aforementioned background, the current systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs evaluated the effects of WBV on three major components of exercise performance in athletes: power, strength, and cardiovascular endurance.

Methods

Information Sources

The protocol for this study was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42022371545). The findings are reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Appendix 1A and Appendix 1B) (Page et al., 2021). A librarian of our research team systematically searched multiple databases for relevant articles published from database inception to April 2024.

Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: having an RCT design, involving healthy adult (15–40 years, excluding children) athletes of any sex or race who professionally or recreationally engaged in sports (e.g., ballet, basketball, sprinting, and volleyball), and assessing the effects of WBV. The search was not restricted by language. We included RCTs in which WBV was implemented (as part of exercise training) for at least two weeks (Ashton et al., 2020). Although a recent study showed acute WBV could activate either the sympathetic or the parasympathetic nervous system (Tan et al., 2024), evidence suggests that a minimum of two weeks of training can improve heart rate reserve and maximum oxygen uptake (Borresen and Lambert, 2008).

The exclusion criteria were as follows: including individuals with comorbidities or those with previous experience in WBV, having a complex WBV protocol, involving a combination of vibration types, assessing only the immediate effects of only one or few sessions of WBV, and having a single-arm or a crossover design.

The inclusion criteria were defined using the following Participant, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome, Time, and Study design framework. Participants were healthy athletes who professionally or recreationally engaged in any sports. The intervention was WBV, including synchronous vertical (SV) or side-alternating (SA) vibrations. The control group received conventional training without WBV. The outcomes were CMJ height, SJ height, isometric and concentric torque of the knee extensors and flexors, and VO2max during aerobic exercise. The intervention duration was >2 weeks. The target study design was the RCT.

Search Strategy

Two reviewers (Y.-C.P. and Y.-T.G.) used the keywords “whole body vibration” AND (“athletes” OR “sports” OR “exercise”) to search for relevant RCTs in the independently searched PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, and Chinese Electronic Periodical Services (CEPS) databases using appropriate keywords for relevant articles published from database inception to April 20, 2024. In addition, ISRCTRN Registry, Clinicaltrials.gov, and Open Science Framework were searched for articles published during the same period. The search strategy is presented in Appendix 2.

Selection and Data Collection Processes

The same two researchers independently evaluated all retrieved abstracts, studies, and citations and subsequently discussed their findings. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (W.-H.H.). Y.-C.P. and Y.-T.G. independently extracted the following data: the study country, the sport type, sample size, athlete age, interventions in the experimental and control groups, and WBV protocols and variables (e.g., vibration type, peak-to-peak displacement, and the body position). Of the potentially eligible articles, we identified and removed duplicate publications and those that did not have full-text availability. At the title-abstract stage of screening for eligibility (stage I), we excluded articles on the basis of their titles and abstracts, respectively. At the full-text stage of screening for eligibility (stage II), we excluded several articles because of the following reasons: did not enroll athletes, did not use a parallel design, had intervention duration of <14 days, or assessed outcome indicators not measured by any other study.

Data Item

To evaluate the effects of WBV training, we measured the athletes’ exercise performance before and after the intervention. Seven indicators were used to assess three key components of exercise performance: CMJ and SJ height (power), isometric and concentric torque of the knee extensors and flexors (strength), and VO2max during aerobic exercise (cardiovascular endurance).

Study Risk of Bias Assessment

Two reviewers (Y.-C.P. and Y.-T.G.) independently assessed the risk of bias using the revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for RCTs (version 2; Bristol, England, UK) (Sterne et al., 2019). This tool can be used to evaluate risks of bias in six distinct domains: the randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, outcome measurement, result selection, and overall bias. Each domain includes specific questions for measuring potential bias, with response options of “yes”, “probably yes”, “probably no”, “no”, and “no information”. In this study, each domain was categorized as having a low risk of bias, a high risk of bias, or some concerns. Any between-reviewer disagreements were resolved through discussions with a third author (W.-H.H.). The Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) criteria were used to evaluate the certainty of evidence for the study outcomes (Guyatt et al., 2011).

Effect Measures and Synthesis Methods

All statistical analyses were performed using a random-effects model in RevMan (version 5.4.1), which offers the statistical program MetaView for data visualization. Mean difference and 95% confidence interval (CI) values were calculated for each RCT and are presented in forest plots. If the standard deviation for post-intervention changes or the actual correlation coefficient was not reported, a correlation coefficient of 0.8 was used to estimate the standard deviation for changes from baseline (Higgins et al., 2019). To assess heterogeneity, I2 statistics were calculated; an I2 value of >50% indicated substantial heterogeneity. The potential small-study bias was visually examined using funnel plots (Song et al., 2002). Significance was set at p < 0.05; for publication bias, the threshold was set at p < 0.10.

For articles presenting only graphical data, values were estimated from figures using WebPlotDigitizer (version 4.5) (Rohatgi, 2023). Data were analyzed using RevMan (version 5.4.1; Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK).

The present study did not involve human participants and thus did not require Institutional Review Board approval.

Results

Study Selection

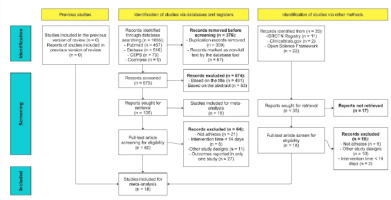

Figure 1 presents a flowchart (following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses 2020 guidelines (PRISMA 2020)) depicting the processes of article screening and selection. As mentioned, we also searched the grey literature, which included preprint articles, conference abstracts, study register entries, clinical study reports, dissertations, unpublished manuscripts, government reports, and any other documents providing relevant information. Of the potentially eligible articles, 376 were excluded before screening because they were duplicate publications (309) or they did not have full-text availability (67). At the title-abstract stage of screening for eligibility (stage I), we excluded 491 and 83 articles on the basis of their titles and abstracts, respectively. Moreover, 23 articles could not be retrieved and were thus excluded. At the full-text stage of screening for eligibility (stage II), we excluded 64 RCTs because of the following reasons: 21 did not enroll athletes, 11 did not use a parallel design, 5 had intervention duration of <14 days (insufficient period for noticeable changes in outcomes), and 27 assessed outcome indicators not measured by any other study. Finally, 18 studies meeting the inclusion criteria were considered in our meta-analysis.

Study Characteristics

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the included studies. Table 2, Appendix 3 and Appendix 4 present the characteristics of the WBV protocols used in the included studies. The presentation adhered to the recommendations of the International Society of Musculoskeletal and Neuronal Interactions (Rauch et al., 2010). The 18 RCTs were published between 2005 and 2022 (Annino et al., 2007; Arora et al., 2021; Bertuzzi et al., 2013; Celik et al., 2022; Cheng et al., 2012; Delecluse et al., 2005; Di Giminiani et al., 2009; Fagnani et al., 2006; Fort et al., 2012; Karatrantou et al., 2013; Kvorning et al., 2006; Lamont et al., 2011; Martinez-Pardo et al., 2013; Oosthuyse et al., 2013; Roschel et al., 2015; Rubio-Arias et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2014). The sample sizes of the studies ranged from 14 to 38. Our analysis included 392 athletes (intervention group: 208; control group: 184). The intervention duration ranged from 3 to 15 weeks. Most studies used synchronous vertical vibrations (n = 14) or side-alternating vibrations (n = 2). Two RCTs did not provide detailed information on the vibration type. Our study focused primarily on young athletes. The settings used for our analysis were based on the included RCTs.

Table 1

Characteristics of the included studies.

[i] M, male; F, female; Y, year; SD, standard deviation; EG, experimental group; CON, control group; WBV, whole-body vibration; NA, data unavailable; CMJ, countermovement jump; VO2max, maximal oxygen uptake; SJ, squat jump; CKE, concentric knee extension; CKF, concentric knee flexion; IKE, isometric knee extension; IKF, isometric knee flexion

Table 2

Protocols and variables related to the WBV intervention.

Risk of Bias in Included Studies

Regarding the outcome exercise performance, our risk-of-bias analysis indicated a low risk of bias for eight RCTs, some concerns for nine RCTs, and a high risk of bias for one RCT (Figure 2). Specifically, in domains 1–3, some concerns were noted for one, three, and six RCTs, respectively, because of factors such as nonrandomized group assignment, a single-blind study design, intragroup differences in exercise, and participant attrition. All 18 RCTs had a low risk of bias in the outcome measurement and result selection domains. Because the assessors were blinded in all RCTs, the studies were considered to have a low risk of detection bias. Studies that reported unadjusted, raw data for outcomes were regarded as having a low risk of reporting bias.

Results of Particular Studies

We measured seven indicators of exercise performance in athletes: CMJ height and SJ height for power, isometric and concentric torque of the knee extensors and flexors for strength, and VO2max during aerobic exercise for cardiovascular endurance.

The pooled effect size of 10 RCTs for CMJ height was 0.66 cm higher in the intervention than in the control group (95% Cl: −0.13 to 1.44; p = 0.1; I2 = 68%). The pooled effect size of five RCTs for SJ height was 0.44 cm higher in the intervention than in the control (95% Cl: −0.45 to 1.33; p = 0.33; I2 = 67%). However, the between-group differences were non-significant for both variables. Furthermore, moderate heterogeneity was observed for these variables (Figure 3a,b).

The pooled effect size of three RCTs for VO2max was −1.18 (95% Cl: −4.25 to 1.89; p = 0.45; I2 = 36%). Therefore, improvement in oxygen uptake was smaller in the intervention than in the control group; however, the between-group difference was non-significant (Figure 3c).

The pooled effect size of four RCTs for isometric torque of the knee extensor was 11.79 N•m (95% CI: −6.08 to 29.66; p = 0.20; I2 = 64%). The pooled effect size of three RCTs for isometric torque of the knee flexors was 6.19 N•m (95% CI: −1.32 to 13.69; p = 0.11; I2 = 39%). Therefore, the intervention and control groups did not differ significantly in terms of changes in the isometric torque of the knee extensors and flexors (Figure 3d,e).

The pooled effect sizes of three RCTs for concentric torque of the knee extensors and flexors were 8.86 N•m (95% CI: 6.00 to 11.72; p < 0.00001; I2 = 0%) and 9.56 N•m (95% CI: 7.4 to 11.72; p < 0.00001; I2 = 0%), respectively, higher in the intervention than in the control group. Notably, no heterogeneity was observed for these variables (Figure 3f,g).

Results of Syntheses

Funnel plots for the seven indicators used in this study are presented in Figure 4. No significant heterogeneity was observed for VO2max, concentric torque of the knee extensors or flexors, or isometric torque of the knee flexors. However, for the two indicators of power (CMJ height and SJ height) and one indicator of strength (isometric torque of the knee extensors), some heterogeneity was observed, with distribution beyond the two diagonal lines (Song et al., 2002).

The GRADE results are presented in Appendix 5. Overall, the quality of evidence supporting the positive effects of WBV on VO2max, isometric torque of the knee flexors, and concentric torque of the knee extensors and flexors was low. Moreover, the quality of evidence supporting the positive effects of WBV on CMJ height, SJ height, and isometric torque of the knee extensors was very low.

Discussion

Overall Effects

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis of the effects of WBV on three major components of exercise performance in athletes: power, strength, and cardiovascular endurance. WBV has been extensively studied for its potential to enhance athletic performance (Alam et al., 2018; Coelho-Oliveira et al., 2023; Hortobagyi et al., 2015; Minhaj et al., 2022).

Mechanical vibration applied during WBV induces cyclic transitions between eccentric and concentric muscle contractions, eliciting a neuromuscular response (Rauch et al., 2010). WBV has been reported to enhance muscle strength, power, and endurance (Alam et al., 2018). The WBV-mediated increase in muscle activity is mediated by several neural mechanisms, such as hormonal factors, TVR activation, and alterations in proprioceptor discharge (Da Silva-Grigoletto et al., 2009). Among these, the most commonly reported mechanism is TVR activation, which occurs during direct vibratory musculotendinous stimulation (Nordlund and Thorstensson, 2007). The TVR, triggered by vibratory stimulation of muscle spindles’ Ia fibers, leads to muscle contractions (De Gail et al., 1966; Hagbarth and Eklund, 1966) through both monosynaptic and polysynaptic pathways (Desmedt and Godaux, 1978; Matthews, 1966).

Physiologically, WBV is theorized to enhance exercise performance by stimulating muscle contractions (Rigoni et al., 2022; Ritzmann et al., 2010). This stimulation may enhance muscle activation, thereby increasing muscle strength (Masud et al., 2022). Some researchers have suggested that WBV expedites recovery by reducing muscle soreness and improving metabolic waste clearance from muscles after intense exercise (Herrero et al., 2011; Mahbub et al., 2019). Regarding cardiovascular endurance, researchers have proposed that WBV increases metabolic activity by increasing muscular activity (Rittweger et al., 2001). This effect is similar to the increase in the heart rate and lactate concentration that occurs during aerobic exercise (Crevenna et al., 2003).

Empirical studies have demonstrated the positive effects of WBV on athletes’ lower-limb muscle strength (Colson et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2014). For example, Annino et al. (2007) reported that short-term WBV effectively improved explosive knee extensor strength in elite ballet dancers. Conversely, Kvorning et al. (2006) reported that compared with conventional resistance training alone, a combination of WBV and conventional resistance training led to no additional improvements in maximal voluntary isometric contraction and mechanical performance. A meta-analysis suggested that WBV effectively increased lower-limb strength, but not upper-limb strength, lower-limb power or overall muscle endurance (Gonçalves de Oliveira et al., 2023). Another meta-analysis highlighted the lack of sufficient evidence supporting the positive effects of WBV on neuromuscular performance of individuals with spinal cord injuries (Ji et al., 2017).

In our study, WBV significantly affected concentric extension and flexion muscle strength in athletes. The RCTs assessing these two variables employed the side-alternating mode of WBV, in which one foot was elevated relatively to the other, causing alternating movements between feet (Bidonde et al., 2017) and thus inducing rotational movements around the hip and lumbosacral joints (Rittweger et al., 2002). Such movements introduced an additional degree of freedom in the side-alternating WBV mode. Thus, whole-body mechanical impedance was lower during horizontal vibration than during synchronous vertical WBV, where vibration was applied simultaneously to both feet (Abercromby et al., 2007). None of the RCTs included complex WBV types, such as stochastic resonance WBV, or combined synchronous vertical and side-alternating vibrations. Stochastic resonance WBV is commonly used for older individuals because of its safety profiles; for example, it does not lead to exhaustion, and it helps maintain low blood pressure and lactate levels during training (de Bruin et al., 2020; Rogan and Taeymans, 2023).

Regarding the amplitude of WBV, our findings corroborate those of studies suggesting that an amplitude of 4 mm is optimal for clinical use (Al Masud et al., 2022; Stania et al., 2017).

Muscle Power: CMJ Performance and SJ Height

The CMJ, a vertical jump, is used to assess power during training, for performance monitoring, and in research as an indicator of power output (Dobbs et al., 2015). During the CMJ, athletes flex their knees and hip joints to reach a quarter squat position before rapidly extending these joints to achieve the maximum jump height (Suchomel et al., 2016). The CMJ can be performed with or without an arm swing; nevertheless, incorporating the arm swing can enhance performance by >10% after WBV (Cheng et al., 2008; Feltner et al., 1999). CMJ performance is associated with maximal speed, maximal strength, and power. Jump height was reported to be a robust indicator of peak power (Cheng et al., 2008). Another variable commonly used to assess lower-body power is the SJ (Young, 1995). During the CMJ, the athlete moves downward from a standing position; this is immediately followed by an upward movement (takeoff). By contrast, during the SJ, the athlete descends into a semi-squat position and holds this position for approximately 3 s before the takeoff (Van Hooren and Zolotarjova, 2017). CMJ height tends to be greater than SJ height. This discrepancy may be attributable to the countermovement phase, which enables muscles to achieve increased levels of activity (fraction of attached cross-bridges) and force before the beginning of the shortening cycle; this enhances muscle performance during the initial phase of the jump (Bobbert et al., 1996). In our study, both CMJ height and SJ height exhibited non-significant increases after WBV. Because the control group received only conventional training, WBV might have exerted minimal or negligible additional effects on muscle power.

Muscle Strength: Isometric and Concentric Torque of the Knee Extensors and Flexors

WBV has been reported to improve muscle strength of the knee extensors and flexors in athletes (Colson et al., 2010; Karatrantou et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2014). A study reported that vibration increased muscle activity in various lower-limb muscles; however, overall, no prominent dose-response relationship was observed between WBV acceleration or frequency and muscle response (Tankisheva et al., 2013). A meta-analysis indicated that WBV considerably improved strength of the knee extensors and flexors, hip extensors, and ankle plantar flexors in older adults (Gonçalves de Oliveira et al., 2023). A review highlighted that at high frequencies and amplitudes, WBV may be beneficial for training the quadriceps muscles (e.g., rectus femoris, vastus medialis, and vastus lateralis) and lower-limb posterior muscles (e.g., biceps femoris); however, the optimal frequency and amplitude remain to be determined (Al Masud et al., 2022). We observed significant improvements in the concentric torque of the knee extensors and flexors after WBV. However, isometric torque of these muscle groups exhibited no significant improvements. The improvement in strength may be attributable to the WBV-mediated activation of the TVR. Muscle stretching due to vibrations activates muscle spindles, eliciting a response similar to the traditional stretch reflex (Bosco et al., 1999). This increases electromyography activity (Di Giminiani et al., 2015; Ritzmann et al., 2010) and force production (Couto et al., 2012; Silva et al., 2008).

Cardiovascular Endurance: VO2max

Athletic performance and overall fitness are extremely dependent on cardiovascular endurance, which enables athletes to effectively perform across various sports. VO2max, the gold standard for measuring aerobic fitness, assesses an athlete’s maximal oxygen utilization during intense exercise (LeMond and Hom, 2015). It serves as a reliable indicator of the cardiorespiratory system’s capacity to deliver oxygen to muscles during physical exertion under specific conditions of fitness and oxygen availability (Bertuzzi et al., 2013). VO2max is correlated with performance in endurance activities such as distance running (Joyner and Coyle, 2008).

Our study revealed no significant improvements in VO2max after WBV in athletes. This finding suggests that vibration exercises do not induce the same cardiovascular adaptations noted with conventional aerobic exercises. Our findings can be related to the fact that WBV may insufficiently enhance maximal aerobic power in trained athletes, possibly because the intensity of WBV training is typically <50% of VO2max (Bertuzzi et al., 2013; Hurley et al., 1984). Our results are consistent with conclusions from a Cochrane review, which highlighted the lack of sufficient evidence supporting the potential of WBV to improve the heart rate and lung function compared with the benefits of conventional aerobic exercises (Bidonde et al., 2017).

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of the present study are its literature search strategy, which enabled retrieval of relevant RCTs conducted over a long period, and its assessment of performance indicators that may be influenced by WBV.

This study, however, has also some limitations. First, the quality of the included RCTs raised concerns; >50% (10/18) of the included studies presented some concerns or a high risk of bias. Furthermore, assessments based on the GRADE criteria revealed that the certainty of evidence was low or very low for all seven variables. The aforementioned factors likely reduced the reliability of our results. Second, some heterogeneity was observed among the RCTs because of variations in WBV settings (e.g., vibration amplitude, frequency, type, duration, and repetitions) and protocols (e.g., intervention duration, assessment time points, study country, and sport type). For example, a previous study has shown that a rest interval of 4 min resulted in significantly higher CMJ values than a rest interval of 2 min in highly trained karate practitioners (Pojskic et al., 2024). Moreover, differences in body composition and activity levels between men and women might have influenced the effects of WBV on exercise performance. Finally, the diverse range of sports included in the RCTs likely involved different exercise intensities; this discrepancy might have influenced our results.

Conclusions

In our review of 18 RCTs, we investigated the effects of WBV on athletes’ exercise performance. Our meta-analysis revealed significant differences in the pooled estimates for the concentric torque of the knee extensors and flexors between the intervention and control groups. However, the overall quality of the evidence supporting these findings was low. Furthermore, we observed no significant post-intervention improvements in the indicators of power and cardiovascular endurance. Overall, our findings suggest that the current evidence is insufficient to enable provision of clear and generalized recommendations regarding the efficacy of WBV in improving athletes’ exercise performance. To provide evidence-based guidance for WBV, future studies should consider participants’ characteristics as well as intervention frequency, intensity, and duration in their analysis.